Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (00:00)

While genetics have been recognized as playing a part in substance use disorders, as well as mental health and behavioral health, we’re still gaining awareness as to exactly how they’re playing a role. And in this conversation with Dr. Danielle Dick, we get to learn about the way that genetics can really be instrumental in the prevention, intervention, and treatment of substance use disorders, mental health, behaviors, all these different components that go into who a person is and how they can go about living their best life.

Stay tuned as we continue to reduce the stigma.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (01:42)

and welcome to Recovery Conversations. Today’s conversation is with Dr. Danielle Dick, Director of the Rutgers Addiction Research Center in the Brain Health Institute, the Greg Brown Endowed Chair in Neuroscience, Professor of Psychiatry at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, and the author of The Child Code. That’s a lot of very formal titles there, Dr. Dick. Can you please share with us who you really are?

Danielle Dick (02:08)

Absolutely. It’s a pleasure to be here with you today, Whitney. Thank you so much for inviting me on. This is a topic that’s near and dear to my heart. So my primary day job is that I run the Rutgers Addiction Research Center, which is the largest addiction research center in the world. There’s actually nearly 150 researchers who are spanning all the way from basic science,

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (02:13)

Thank you for coming.

Danielle Dick (02:34)

through to studying epidemiology, etiology. So what causes some people to be more at risk? What do patterns and consequences of substance use look like across time to treatment and recovery all the way through to policy? And so we really kind of span the translational spectrum, which I think speaks to the need to bring people.

who come from a variety of different perspectives and backgrounds and who are looking at this really complex problem from different angles so that we can work together to ultimately reduce the burden of addiction in our society.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (03:12)

That’s absolutely, by having so many different partners involved in looking at each facet, it’s really looking at that whole person as well as the systems that they’re within. And what led you down the pathway that, you know, eventually led to your work at Rutgers?

Danielle Dick (03:31)

So I am someone who is always interested in how can I have an impact and how can I make a difference as I think many of us in this field are. And I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia 25 plus years ago. And I was working on a psychiatric unit. And at that time, I thought I wanted to go into clinical practice. I was going to go on and become an MD. And

What I really became frustrated by, you know, concerned about was the revolving door aspect of psychiatry, that people will get better and then, you know, we would essentially patch them up. They would go back out and then we’d see them back again on the psychiatric unit. And it really drove my interest and passion in research. So how can we better understand?

what’s causing these problems so that we can prevent them before they start, and how can we develop better treatments, better support people in recovery. And so, you know, I developed my own program of research, but as you become more senior, then I also became interested in how at a programmatic level do we bring people together to do really interesting things that we can’t do on our own. And so that’s how I ended up directing this large research center.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (04:57)

Again, it speaks to just the need that we need to recognize every component about the disease, but also about the person by bringing all those. I’m curious, you know, addiction research center that is clearly doing a lot, right? Looking at systems, looking at prevention you mentioned, what have been some of your favorite collaborations with other professions through your research?

Danielle Dick (05:26)

Yeah, so maybe I’ll start with a project that we’re working on right now, which is we know that individuals who are in treatment are a really heterogeneous group. We know that people start using substances for different reasons. They probably carry different genetic risks, different environmental and sociocultural factors that led to having challenges. And so then an individual shows up at treatment with all these differences.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (05:30)

Sure.

Danielle Dick (05:55)

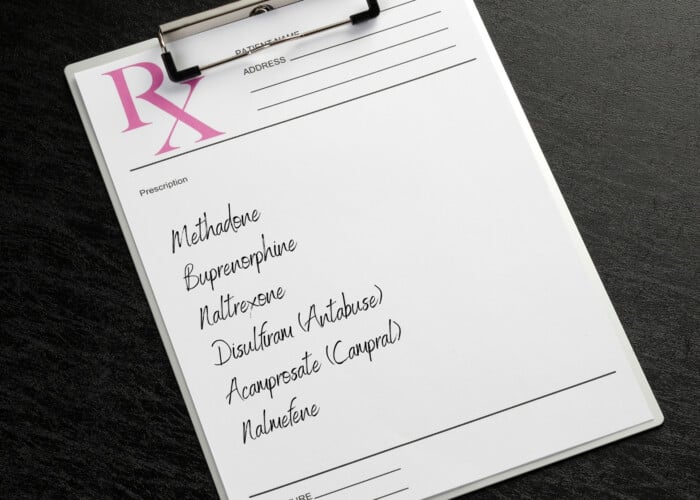

And yet very often, even with best practice treatment, we’re essentially kind of trying to figure out what’s gonna work best for an individual. Most of medicine now is a one size fits all. We try, here, this is what works best for most people. And then we kind of, is it working for you, not working for you? Well, we’re gonna try something else here and see if that works better. This whole process is incredibly costly. It’s costly to the individual who’s suffering, it’s costly to the family.

It’s costly to our healthcare system. And of course we know that it’s true of all of medicine, but it’s alive and well in substance use and mental health disorder treatments. And so what we’re launching right now is at Rutgers, we’re actually launching what we call the research community partnership. And so one of the things that I dislike about our field is that we are so siloed, even when we all are working on,

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (06:53)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (06:54)

substance use problems and challenges and want to fix them and make things better. We’ve got researchers over here and candidly even researchers are siloed in terms of the genetics folks are separate from the folks who study psychology or who study environmental factors or community factors. And then we’ve got our clinicians who are in the trenches working who often are not talking to the researchers and vice versa. And then we’ve got our patients who, you know,

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (06:56)

Great.

Danielle Dick (07:23)

very often are not connected to this whole network as well. And so the research community partnership, the whole idea is how do we bring together researchers, clinicians, and patients and family members, and candidly, the broader community of anybody who cares about this, so that we can all be a part of the process of discovery and making things better. And so by that, what we’re essentially doing, and we’re piloting it right now with some of our Rutgers,

clinics, but the hope is that soon we’re going to start opening it up to more and more clinics. We’re going to invite patients and family members, friends, whomever to sign up to be a part of the partnership. And you essentially provide your contact information. And what you are agreeing to is, I want to be contacted by researchers. I want to understand more about and potentially contribute to the process of discovery. And so.

You can fill out short surveys and you can also agree for those who are interested to share their health records. And that increases the chance that you’ll get selected for studies because of course some studies are looking for individuals who smoke or other studies might be looking at individuals who have a history of depression in addition to substance use challenges, et cetera. And so the whole idea is that you’ll get invited to different studies.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (08:29)

Okay.

Danielle Dick (08:52)

you can agree to be a part or not of anyone that interests you. And then regardless of whether or not you’re participating in projects, we’re going to essentially be giving newsletters, sending out newsletters on a semi -regular basis with here’s what’s new in addiction, here’s what we’re finding, you know, other kind of events and helpful pieces of information for individuals and families. And of course we want the clinicians to be a part of this.

So we will be working with them on the research projects, the research findings, as well as the patients and our community advisory board. And so it’s really kind of a, the idea is to create this partnership that brings us all together in being invested in, you know, discovery of new treatments, new preventions, how do we better support people and getting that information out to people, out to patients, community, to

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (09:41)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (09:51)

clinicians and to having clinicians and community members having more interface with the researchers. So our research can also be more impactful, more meaningful as well. So we’re starting that and the very first set of individuals who are enrolling, we’re actually inviting them to be part of we have a cutting edge neuroimaging center. And so it would be to come in and essentially do brain scans.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (10:15)

wow.

Danielle Dick (10:19)

We have a large genetics group. That’s my own particular area of research. So to give a saliva sample, you know, you spit in a tube and we can genotype to essentially look at different genetic risk factors and then to essentially complete surveys, some of which we’re doing in kind of real time using digital data collection through Fitbits, through, you know, quick surveys that you might do throughout the day on your phone.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (10:23)

Mm -hmm.

Danielle Dick (10:48)

And all of this is looking at trying to figure out who responds best to treatment. So can we help use all of these advances to understand who needs maybe some additional supports? Are certain types of treatment better for certain individuals? And with the digital data collection piece, how can we real time identify individuals when they might be struggling?

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (11:03)

Right.

Danielle Dick (11:15)

And so it’s not just, you know, your regular groups, which are Tuesdays at 10 a or whatnot, but we could get help to an individual as they are at that sort of crisis point or starting to feel unsettled and where they are in their recovery. Exactly. So that is just one example of the kinds of projects that were really spearheading through the center that bring together all of these different components. And the piece I actually,

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (11:21)

Right.

before there’s a full decline, right? Wow.

Danielle Dick (11:45)

didn’t mention there is that we have a whole neuroscience group who does work in model organisms because as we identify genes and brain circuits, we also then want to be able to use that to better understand how they work. We can of course do things in animals that we can’t do in human brains. And so to be able to develop better pharmaceutical targets as well too. So that.

kind of spans that whole, all the way from basic science through to our patients in our clinics.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (12:19)

First and foremost, I want to sign up for a newsletter if I can, because this sounds amazing and really is eliminating a lot of barriers between the individuals who are living maybe with substance use or mental health and their treatment providers and the knowledge base. Because, you know, as a counselor, as well as someone with mental health diagnoses, with for me, you know, it’s finding a valid and reputable source.

But I’ve also been frustrated at times because as you would know better than me, the publication process can take years, research can take years. And so then the dissemination can be delayed. And it sounds like you’re really expediting and accelerating getting the information to the people who need it and then can apply it either to patients or can use it to advocate for potential different approaches for their own treatment or a loved one’s treatment. That’s amazing.

Danielle Dick (13:18)

That’s one of the things that I’ve become really passionate about over my career. I sometimes jokingly call it my mid -career crisis, where I realized that as researchers, the vast majority of our time is spent talking to other researchers. So we write up our scientific studies and results for publication in scientific journals that are read by other researchers. We go to academic conferences and present our work to other researchers.

And so I had this moment where I thought, how is this work actually getting into the hands of people who can use it? Because in all of my grants, a lot of my time is spent writing grants to the National Institutes of Health, talking about, you know, here is the cutting edge kind of next things we need to do to better understand and address substance use disorders. And in all of those grants, I have some sentence about,

My own work, as I mentioned, is in genetics, better understanding how genetic and environmental influences come together to contribute to why some people are more at risk than others will ultimately help us develop better prevention, intervention, and treatment. And then I realized, but all the people who are doing prevention, intervention, and treatment, they’re not reading genetics journals, you know? I mean, at best, maybe they’re reading journals that are specifically talking about new treatments or treatment studies.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (14:39)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (14:46)

But we are so in our own worlds and clinicians of course are so in the trenches. You know, very often we know, you know, overworked, understaffed, they don’t have time to be going out and reading all the, you know, publications that are coming out constantly. And so one of the things that I really try to do is to bring research to the public in ways that are understandable. And so if you go to my website,

DanielleDick .com. I write a variety of blogs for Psychology Today and Medium, and I will put, you know, talks that I’ve given to communities and other sorts of things up there. So the whole idea is how do we get research out? One of the areas that this has come up is when I became a parent, I discovered that so much of the popular press parenting information that’s out there, which candidly,

I hadn’t paid a lot of attention to because I study kids’ development. But when I became a parent and I started to pay attention, I realized how much of the research was not getting out there, especially in my particular area, which is genetic and environmental influences on kids’ behavior, on really all of our outcomes. But of course, our genes don’t just show up when we’re adults. You know, they start influencing kids’ behavior early on.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (16:07)

Right.

Danielle Dick (16:13)

And so that led me to write my book, The Child Code, which came out in 2021 from Penguin Random House. And it really is all in service of how do we get research to people who can use it.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (16:29)

And I’m glad that you brought up the child code because, you know, my awareness with it is that it’s really similar to what you were talking about with finding, you know, ways to best serve the individual, whether it’s at a genetic level or what have you. The child code talks about how to best parent a child in a way, based off of their maybe genetic predispositions, but also how they, their behaviors present.

Can you speak a little bit more about how you’re using genetics to really drive individualized care, individualized parenting?

Danielle Dick (17:09)

Absolutely. So one of the things that I found so eye -opening when I became a parent is that I saw my highly intelligent, capable, largely mom friends, if their children were not turning out to be the perfect, dreamy human beings we all imagine having before we have children, they were riddled with self -doubt. And so especially if their children were struggling,

whether that is just kind of what we, I might call normative struggles that parents have or struggles that are truly associated with, you know, mental health or substance use challenges. There was a lot of self doubt, a lot of what am I doing wrong? What did I do to cause this in my child or, or what did I not do that my child is struggling? And.

I also found myself raising the high risk child that I study, the irony, highly impulsive, highly emotional. And so for me, knowing the research was so helpful, but I looked around and I saw how many people didn’t know the research and were really struggling as parents. And a lot of my research is really on how much of

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (18:08)

Hahaha.

Danielle Dick (18:27)

children’s behavior, how much of our life outcomes is influenced by our genes in addition to our environmental factors. And so for almost any behavior that you’re interested in, whether it’s substance use disorders or whether it’s impulsivity in children or anxiety, you know, I sort of jokingly say the rule of thumb is that it’s going to be about 50 -50, meaning it’s about

50 % heritable and about 50 % environmental factors. And to be clear, what that doesn’t mean is that for any one individual, you know, half of the reason, for example, that I’m impulsive or that I’ve developed, you know, a substance use disorder is because of my genes and the other half is because of my environment. What it means is at the population level, if you, when you look around and you go, why are some kids more impulsive?

and others are not. Why are some kids really anxious and others are not? Why do some people develop depression or substance use problems and others don’t? About half of the reason is differences in their DNA and about half of the reason is differences in their environments. And, you know, as when it comes to our parenting, it’s as if we have forgotten that genetics piece of things.

And so it’s like we double down on, okay, you know, it’s all on me. I’ve got this. And, and I think that’s a real problem for two big reasons. The first is what I sometimes call the parenting myth, which is the idea that if you are just a good enough parent, if you just do all the things right, if you read all the books and you watch your, you know, Instagram favorite mom influencers and all the things.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (19:49)

Great.

Danielle Dick (20:18)

that you’re going to be able to parent that child, you know, right into the Ivy league school or the Nobel prize. And that’s just, there’s no evidence that we have that any environmental influences have that much of an impact. Unfortunately, the environmental influences that sort of single -handedly seem to have a huge impact are adverse environmental influences, right? Are severe traumas and things of that sort. But.

The evidence that we can super parent our children into like extremely great outcomes, there’s no evidence for that. And by sort of whether it’s conscious or unconscious adopting this, I really need to be the best possible parent for my child to have the best possible outcome. You know, it creates a lot of pressure on us. We can create a lot of pressure on our kids who feel the weight of our expectations.

And I think the other piece is that it can contribute to this culture of judgment. This, you know, you see that toddler that’s throwing a fit or the teenager that’s talking back and you, you know, look at that teenager or toddler and you look at their parent, you think that parent really needs to, you know, fill in whatever your favorite parenting advice is. And of course, substance use and mental health challenges is an area where we don’t need any more stigma. We don’t need any more judgment.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (21:21)

Great.

No.

Danielle Dick (21:43)

We need to support people who are struggling. We need to support parents who have kids who are struggling. And so I think that by kind of ignoring the role that genes play in kids’ outcomes, it contributes to more of this kind of judgment and stigma. And the second piece is that I think by ignoring the role of genetics, we also miss an opportunity. And this is really a lot of what the book is about.

to tailor our parenting to what will work best for each of our unique kiddos. And so I just talked a little bit ago about how treatment is an area where we try to do one size fits all. We know that doesn’t work very well, that everyone has their own path to having developed substance use challenges and we need to be thinking about how we can do more tailored treatment. With kids, our kids are all unique.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (22:19)

Yeah.

Mm -hmm.

Danielle Dick (22:42)

They all have brains that are wired in different ways, literally from their genetic codes. And so the idea that there is one best way to parent or one right way to parent, or that if you just follow all these things, your child is going to respond in just the right way. That also totally ignores the fact that they’re all different. But if we pay attention to those differences and really the book is a little bit about.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (22:46)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (23:11)

kind of the science behind how we know how much genes influence kids behavior, how those genes influence their behavior, which also shapes their environments. But it’s got surveys for parents to figure out where their child falls on these kind of three big genetically influenced dimensions. And then it walks through, okay, depending on where your child falls on each of these dimensions, here’s what we know about parenting strategies that work better.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (23:26)

Wow.

Danielle Dick (23:41)

or worse, for kids with different temperamental characteristics.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (23:46)

There’s just so much there that is powerful in and of itself. And I imagine going to be very influential on the development moving forward of the field. Where we are today, obviously, 30 years ago, genetics as part of substance use treatment or mental health treatment was not on the board. We were just starting to recognize genetics in general and seeing from a.

physical health perspective was more recognition, which, you know, it’s more acceptable to have a physical health diagnosis or disease. And so you talked about that stigma and it made me think about, you know, the sense of failure that I’ve heard many parents share whenever a child struggles with mental health or with substance use and the fear of asking for help.

because you don’t want to be looked at as a bad parent, going back to you saying, you know, not recognizing the role of genetics. And so we’ve known now for a while that, you know, substance use and mental health, of course, are diseases. And so I’m curious at what you see as the role of recognizing genetics more and more in these areas with behaviors and things like that, how that can facilitate more

willingness or openness to asking for help.

Danielle Dick (25:17)

Absolutely. So I’ll talk first about parenting and then I will talk about what we know and how I think it can impact treatment as well in terms of how far genetics has come. So on the parenting front, one of the questions I frequently get asked from parents is, is this normal? They’re trying to figure out, is my child quote, just impulsive or do they have ADHD? Are they just more anxious or?

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (25:30)

Yeah.

Danielle Dick (25:47)

Do they have clinical anxiety? And the question, is this normal? I tell parents is the wrong question to be asking because what we know is that behavior is distributed like a bell curve. So whether you’re looking at impulsivity or depression or substance use or anxiety, it’s distributed like a bell curve, meaning that there are going to be some people who are very low.

lots of folks who are in the middle, and it is normal to have some people who are high. The better question to think about is, is this causing impairment in the child’s life? So is it harming their relationship with you, their relationship with their peers? Is it causing them challenges in school? That’s kind of the trifecta. Is it interfering with parents, peers, and with teachers in schooling?

And if the answer to any of those is yes, and in particular to multiple of those, then it is always a good idea to seek help. In fact, the people that I know that are most willing and likely to seek help quickly are other psychologists and psychiatrists because we get, it is so hard to figure these things out with our kids and raising kids is hard and we can all use some extra help. And so,

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (27:06)

Right.

Danielle Dick (27:15)

the kind of like, you know, we all have to make determinations about, gosh, is this just the sniffles? And so they’re going to stay in bed or do I need to take them to the pediatrician? There’s a little bit of that judgment, but, you know, when you’re really worrying, it always behooves you to call the pediatrician. It always behooves you to go out and seek help for mental health concerns that you have in your child as well, too, mental or behavioral health.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (27:22)

you

Danielle Dick (27:44)

So there’s the parenting piece. On the treatment side of things, we have learned a ton in the last decade, even in the last five years, it’s advanced radically about how our genes influence risk for substance use disorders. So we’ve known for some time now that genes do play an important role. I mentioned earlier that about half of the variability between

Why some people are more likely to develop problems than others is due to differences in the DNA sequence they were born with. But what we have been able to do is to, over just the last few years, start identifying the specific genes involved. And so what we know is there is no gene for substance use disorders or depression or anxiety, despite what you sometimes hear in the…

popular press, there’s no gene for any of these complex outcomes. Instead, what we know is that there are likely thousands of genetic variants, each of which just have a small effect on its own. So we now can scan the entire genome and really gene identification at its simplest is you’re comparing individuals who have the disease.

with those who don’t, that’s true whether you’re looking at a cancer or substance use disorder, or you’re comparing individuals who are high on an outcome, impulsivity, or how frequently people use as compared to who are lower. And you’re asking, are individuals who are affected or who are higher more likely to carry a particular version at this location in the genome than individuals who are unaffected?

And so we do this across millions of locations in the genome. We have now identified literally more than a thousand and we can essentially add those up, weight them by how big of an effect. They’re all tiny effects, but how tiny of an effect they have. And we can add that up to create what is often called a polygenic score or a polygenic risk score.

So we can now create those for any one individual. Right now in the, I lead a big international gene identification consortium. And so the most predictive scores that come out of this group that I lead account for about 10 % of the variance in outcomes. And, you know, comparatively,

That’s a lot. Now that’s still 90 % that’s unaccounted for. It’s the environment, it’s other genes we haven’t found yet. But it can certainly, you know, give a sense of are individuals at higher risk, lower risk, or average risk. And not only that, but we have learned a tremendous amount about what are those different genetically influenced risk pathways. And here’s what I mean by that.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (30:28)

Yeah.

Danielle Dick (30:56)

I find that when I talk to people about, you know, our genes influence why some people are more likely to develop problems with addiction than others, people will say, yeah, yeah. But what they’re imagining is that some people’s bodies just respond to a drug in a way that makes it much more addictive, that they’re much more likely to become dependent physiologically on that drug. And there is some small truth to that.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (31:13)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (31:23)

There are some genes that are involved in drug metabolism that influence, you know, how your body responds to alcohol, to nicotine, to opiates, but that is actually just one teeny part. That is the minority of that 50 % of genetic differences between us. The vast majority of the ways that our genes influence

why some people are more at risk than others, isn’t about the way bodies respond to a drug. It’s about the way brains are wired. And so what we talk about is two big genetically influenced risk pathways. One of them is what we call the externalizing pathway. And it is related to how our brains process rewards and consequences. It’s related to, you know, things that we call impulsivity and sensation seeking. And some people are

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (32:15)

Yeah.

Danielle Dick (32:20)

more excited and driven by, you know, that, that what we might sometimes call the rush, the high, the what you want right now. Other people have brains that immediately go, is this a good idea? Let me think through all the consequences. And we know that people that are more prone to kind of the here and now, the novelty seeking, the fun seeking, that that is, by the way, it’s not a bad thing in and of itself.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (32:48)

No.

Danielle Dick (32:49)

Entrepreneurs, CEOs, fighter pilots, all tend to be more risk -taking, more sensation -seeking. But we also know that it can lead individuals to be more likely to experiment and to use drugs in risky ways and be more likely to develop problems, particularly when combined with other challenging life circumstances or other comorbid mental health challenges.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (33:03)

Mm -hmm.

Danielle Dick (33:17)

So that’s kind of one big pathway. It’s more of the how our brains respond to reward. And then the other genetically influenced pathway is what we sometimes call the internalizing. So internalizing meaning kind of what’s going on inside of you. Externalizing is the way you interact with the world. The internalizing pathway is related to how brains are wired toward anxiety or toward worry. And we know we all differ on this too. Some people are just more…

prone to anxiety sensitivity toward worry. And if left unchecked or without the skills to manage or cope with that, then it can lead to using substances as a way to cope and developing problems in that sense. And so, you know, I think that by having learned so much about these different genetically influenced risk pathways and where we’re going, of course, now is the ability to also

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (34:03)

great.

Danielle Dick (34:15)

help people understand which areas of genetic risk they’re carrying. Although even right now, you know, I find when I’m talking to individuals, especially who are in the recovery community or who are in treatment about this, they immediately start identifying, yeah, that’s me, right? I am the one who I, you know, I was impulsive from the time I was young, I had ADHD, and then all of a sudden in high school, I was trying new things. I started running with the wrong crowd.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (34:33)

Mm -hmm, right.

Danielle Dick (34:43)

Maybe then there were some challenging circumstances at home or other things that sort of led to their becoming more involved in substance use. Or other people will go, yeah, I was the person who was always anxious. I never felt comfortable in my own skin. And then all of a sudden I became an adult. I discovered that, wow, substances really took the edge off. And of course, these pathways are not mutually exclusive. You can carry risk across multiple of them.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (35:14)

and I imagine they influence each other as well.

Danielle Dick (35:14)

and

Absolutely. And of course, where I think that even today, this is relevant for treatment is because by understanding something and by being proactive about talking with people about this and, you know, having them think critically about it, about what are the risk factors that you carry? How can you not just address the substance use problem, but how can you think about, OK, this is a natural tendency that I have?

How do I channel that for good, right? How do you maybe channel those impulsive tendencies into other things? Or how do I develop skills and strategies to manage some of those tendencies or to manage, for example, anxiety or things so that I don’t stop using the substance of choice, for example, but all of a sudden now I’m gambling or I’m engaging in risky sex.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (35:49)

Yes.

Danielle Dick (36:13)

or I am now worrying all the time and that’s making my recovery even harder to maintain. When we think about those underlying genetically influenced risk factors, we can help people really think about how are they going to achieve holistic recovery, not just stopping the substance that might be causing problems, but really promoting their health and wellbeing.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (36:39)

I, that, that’s really getting at an up the river solution, right? You know, there’s, I, we know here or here, I’m hearing the prevention piece of we can identify you are at increased risk. That right there is a significant, you know, knowledge to have to be able to be proactive. And I’m hearing because we’re able to identify what specific components of your DNA, of your genetics,

lead you to have that risk, we can help build up those skills so that not only do you have to be worried that if you engage in substance use, you’ll develop an addiction, but also what other areas of life would be positively benefited by building up those skills, being able to harness the impulsivity. So it’s not even just your work is going to positively impact substance use prevention, treatment, and long -term recovery.

it’s also going to impact just the person’s general wellbeing and ability to be successful.

Danielle Dick (37:41)

That’s the goal.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (37:43)

Wow. I, as someone who could never comprehend genetics, I am just so interested. And I’m already, of course, following you everywhere. But how can people follow you? How can they connect with you? Before we wrap up, I want to get that information across.

Danielle Dick (38:05)

Absolutely. So my personal website is danieldick .com. You can find a whole series of different resources on there that I try and make accessible to non -scientists. The Rutgers Addiction Research Center is at addiction .rutgers .edu. If you want to learn more about kind of the broader science. I’m also on Instagram, Twitter, now X, Facebook at Dr. Danielle Dick.

And you can find my book at thechildcode .com or Amazon or other places where books are sold.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (38:43)

I hope everyone goes and starts following you because I think that the biggest takeaway for me has been the plethora of information that is now accessible to the average person. And that really, that is what your work is, is how do we take what has been known at this academic level and translate it to people being able to inform their lives and the life, you know, working with their loved ones as well. And so that has been my big takeaway.

What though would you, if people only take one thing away from this conversation we’ve had, what would you like them to walk away remembering?

Danielle Dick (39:21)

That’s such a good question and so hard to narrow it down to just one. But maybe I will leave folks with this quote from one of my genetic counseling friends. She’s kind of the, they’re the world’s sort of leading genetic counselor for psychiatric outcomes. And they always say, your genes are not your fault and they’re also not your fate.

And so as someone who studies genetic influences on behavior, I really love that. You know, we don’t want to ignore the fact that we all have different genetic dispositions. We’re all at risk for something. For some of us, it’s substance use and mental health challenges. For other people, it will be cardiovascular diseases or cancers. And so by understanding our genetic risk factors, we can both do something about them,

We’re not destined to develop problems. DNA is not destiny. I hope that we can use this research to really harness its potential in prevention, intervention, and treatment, in preventing problems before they happen, in helping people better support their treatment and their recovery process. But I also think it’s really critical that we remind people.

that just because you carry genetic risk does not mean you are destined to develop problems. So thank you so much for having me, Whitney. It’s been a real pleasure to talk with you.

Whitney Menarcheck | she/her (40:57)

Thank you so much. I think that everyone’s going to enjoy this. And as I said, please go follow and educate yourself, share with others, because this is the way that we can really make things happen. Because whenever you have more knowledge, you can better advocate for yourself and for your loved ones. So please, everyone, share the awareness of what you’ve gained today.

pass along the podcast episode and the ways to connect with Dr. Dick to anyone who may benefit because sharing this information is how we continue to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health, substance use disorder, behavioral disorders, all these things that really, as we’re learning, comes down to a big part of our genetics. So thank you so much for being with us today.

Danielle Dick (41:47)

Thank you.